Please enter your email address to view this content.

Contentious research

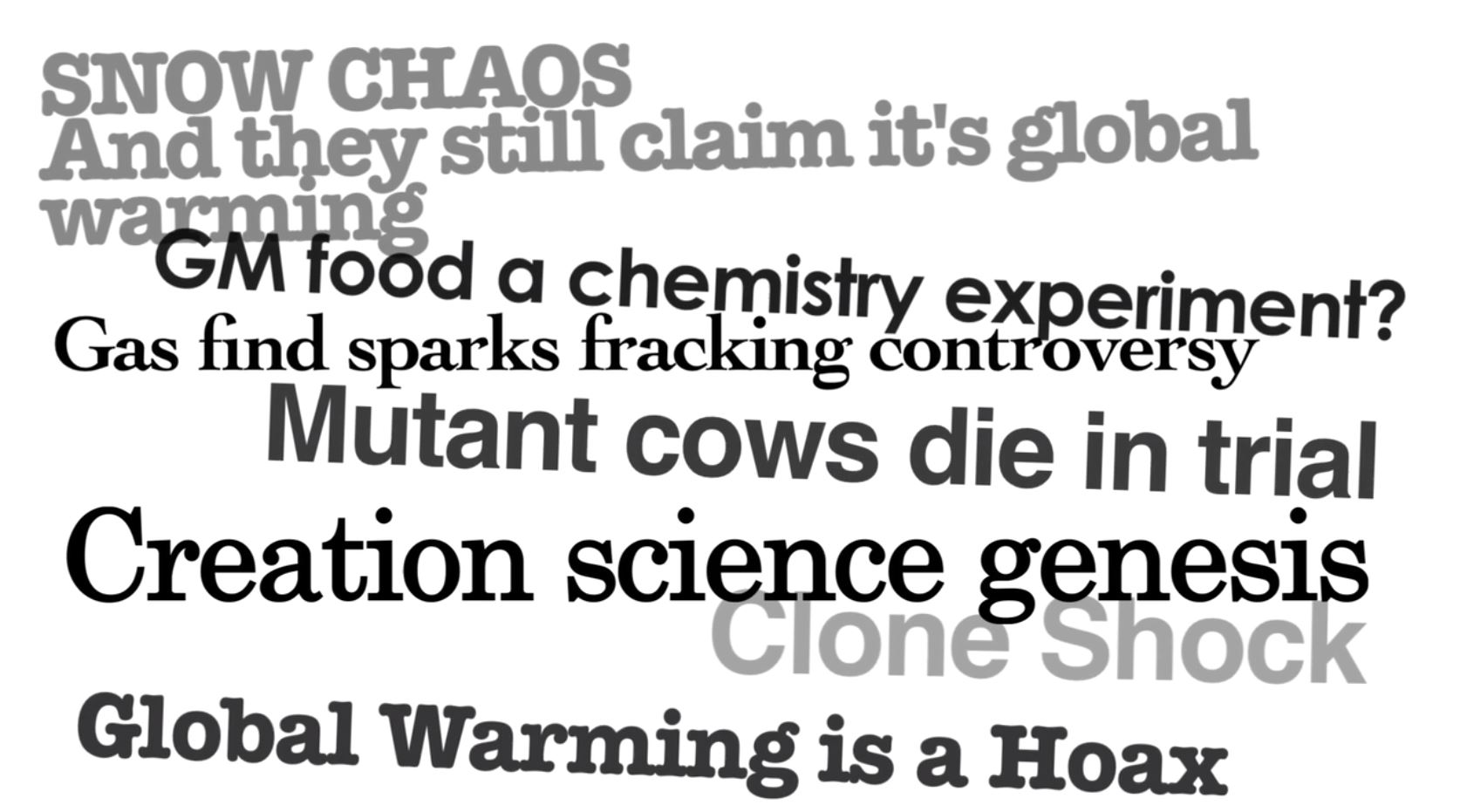

What makes science contentious?

Communicating contentious science

Subjects such as climate change, GM crops, vaccination, and stem cell research are controversial topics. The facts can get lost in emotion, politics, and conspiracies, so it's understandable when scientists decide to steer clear. But researchers must be part of our national conversation.

The biggest risks arise when scientists go in blind, so make sure you understand any underlying issues and how the media works.

This short video explores the issues and hears from scientists working in contentious areas who have braved a media grilling.

Difficult media moments

Many controversial issues have their roots in science, and the media loves to get in the ‘experts’, but doesn’t always treat them well. Scientists can find themselves facing an uninformed but opinionated pundit or an emotional public. That can be daunting, but remembering a few rules can help you survive and even enjoy the experience.

Here we present some fictional scenarios of scientists explaining their work in difficult situations.

A TV tabloid host takes the public's side

Shock jock radio is the most challenging for scientists

Most media interviews with scientists are friendly, but when contentious topics arise the rules can change.

Journalists may adopt an adversarial approach and invite an opposing voice to contribute, even if they represent a fringe view. This can mean fringe views appear as valid to the audience as a scientific consensus, leading to ‘false balance’.

In this situation, make sure that you know your material well, and think about how to engage that particular audience. And prepare to stay calm and address simplistic and unscientific comments, or even aggressive arguments, particularly on talkback radio.

You may believe your science is established fact, but providing facts alone is not enough in contentious areas. People's concerns are rarely about the science, and are more likely to be driven by emotions, which are more persuasive for many than facts.

When the science is divided on an issue, as in vaping research, or, in the case of climate change, it may be presented as divided even though a consensus is established. The media may find a climate sceptic to bill as an ‘expert’ or look for evidence that seems to oppose your view.

When science has become politicised. To justify unpopular policies, politicians sometimes look for 'scientific evidence' to back them up. For example, live exports, climate change, and coal seam gas.

If people believe science has control over their lives, fear and outrage can result. For example, people may feel they're being forced to eat GM foods or that COVID-10 lockdowns are draconian and unneccessary.

Science may support actions the public finds horrifying and indefensible, kangaroo culling for example.

People’s deeply held beliefs and values may lead them to distrust science or believe it is morally wrong, as in embryonic stem cell research or vaccination.

Media interviews or debates on contentious science are not just about winning an argument, they're about the impact you have on the audience. Their views may seem illogical to you, but you need to empathise with their point of view to have any chance of changing their minds:

- Presented with complicated information, people tend to adopt a position based on mental shortcuts and their beliefs rather than scientific evidence, so keep it as simple as you can.

- We're all subject to confirmation bias and seek out and trust information that fits our existing worldview. so we tend to discount information that contradicts those beliefs, avoiding cognitive dissonance. Information that contradicts an established worldview tends to entrench the original beliefs rather than changing minds. So, present facts that appear to fit their worldview - it may help them understand any flaws in their thinking.

- Attitudes that were not formed by facts and logic are not influenced by facts and logic, so don’t expect facts alone to change minds.

- Public concerns about contentious science or new technologies are often not about the science itself, so scientific information is unlikely to allay their concerns. Listen carefully to them. People may be worried about who owns new technology rather than the technology itself, for example. Or there may be ethical concerns or concerns about safety. Acknowledge and address people's concerns in an empathetic way.

- We tend to trust people whose values mirror our own, so be aware you may be perceived as untrustworthy before even opening your mouth based on who employs you and what your work is seeking to achieve.

Some media situations are tough to come out of well, particularly when you're up against an aggressive interviewer. But always remember, it’s the audience you are really talking to rather than the shock jock.

Know your facts but accept they may not be enough to convince people, debate the topic openly and honestly, and make it clear you're aware of and empathetic towards the audience’s concerns. You probably won't win them all over, but hopefully, some will believe you are credible and trustworthy, and they may start looking at the topic in a different light.

Before

- Watch or listen to the program to understand its tone and style

- Ask the journalist if this will be a debate, and whether you'll have to address talkback calls from the public

- Remember the whole experience will be short, so work on summarising the issue, the key facts, and your own position without resorting to jargon or technical language, which will alienate the audience

- Scan media and social media to update yourself on public debate around the issue, and why you have been asked to comment

- Anticipate any tough questions and prepare and rehearse your answers

- Facts don't always change minds, but memorise references and relevant facts, including ‘bigger picture’ statistics by trusted organisations (e.g. the EU on GM crops, CSIRO on climate change)

- Be aware that in contentious media debates, an opposing speaker or group will often rely on:

- Cherry picking data

- Unsubstantiated claims

- Reporting anecdotes as if they are meaningful data

- Highly emotional arguments

- Research the opposing point of view so you can refute their arguments simply and effectively

During

- If possible, negotiate. Ask to have the discussion on your own terms, not at a time or place that puts you at a disadvantage. Ask for a pre-recorded rather than live interview, if possible. Ans ask for a list of questions beforehand

- When faced with an adversarial argument or conspiracy theory, try not to be dismissive. Acknowledge it, refute it briefly, then steer the discussion back to the science

- Don’t get bogged down in ‘my data’ versus ‘your data’. Consider the values behind the audience’s or the opposition’s point of view, and debate based on those values

- Confront highly emotional arguments with responses that acknowledge and address those deeply held concerns

- Talk about the outcomes of the research, rather than the processes involved. Getting lost in detail will distract the audience from your main point, and make you hard to relate to

- Stay calm and stand your ground

Some personal perspectives

In general, the media respects science, but it’s a world with its own rules and deadlines. A journalist’s job is to tell stories that engage their audience and, in the case of a controversial issue to ask tough questions and highlight any conflicts.

Journalists understand why some interviews succeed while others fail, and recognise when hidden agendas are in play. Scientists can learn to cope better in the ‘bear pit’ by learning from them. Their advice on whether to take the plunge or decide discretion is the better part of valour can help you avoid some of the worst outcomes.

Everyone loves a conspiracy - Journalist Tory Shepherd

People are confused by science - Journalist Monica Attard

Choose your battles wisely - Professor Graeme Turner

Performing well requires practice - Dr Gavin Mudd

Most people get their information about science from the media, where nuance is often lost, but this is the arena for public debate. The media's take may seem simplistic to you, but it's vital that the voices of scientists are heard when the discussion is about contentious scientific issues.

Scientists can perform well in media interviews and change minds, but it takes practice and preparation.

- Check out all the different kinds of media, including the outlets you don't like

- Keep up with developments in public debate, and watch how science and politics intersect

- Think about opposing points of view and practice arguing against them simply and without resorting to scientific language

- Come up with succinct, pithy ways to convey your message

- Watch others who perform well, or badly. What did they get right, or wrong? Learn from them

Remember, journalists aren’t scientists

When a journalist approaches you, talk openly with them about the intention of the interview. Ask them what they think the issues are and help them understand if you think they're confused. But avoid being patronising at all costs. Most journalists are highly intelligent people.

Don't forget he media is there to entertain as much as to inform, so they may treat you less than seriously at times. It's best to develop a thick skin and a good sense of humour, but don’t try to out-entertain your host.

Tabloid media may try to set up a scientist as a ‘boffin’. If this happens, stay calm, don’t take the bait, and stick to a few simple facts.

Many people are sceptical and confused about science because it’s highly complex and often seems to disagree with itself. So always try to keep it as simple as possible, and think about how you can help the audience understand.

What most media audiences want to hear from scientists is what a particular scientific development means for them and their lives.

Academics can get bogged down in detail, but what's needed is a different approach - a focus on good storytelling. Think about it in narrative terms - what are the beginning, middle and end of your story? The beginning is the idea you want to convey and why it's important for the public, summarised briefly and simply. The middle is the supporting evidence. And the end is a reiteration of the idea to help it sink in.

More tips from media professionals

Journalists try to tell all sides of a story. They do this to try to provide balance but it means scientists can find themselves up against opposing voices they don’t believe are scientifically credible.

In general, journalists treat their interviewees with respect but there are exceptions, often when issues are contentious. However, scientists must be prepared to go into these difficult situations so their voices are not excluded from the conversations.

Conflict makes news and in the absence of an obvious story, the journalists may opt for an angle of conflict. If scientists can help the journalist understand, identify the 'human' story, and explain it clearly and simply, the conflict may be resolved before it begins.

Certain media experiences such as talkback radio, or facing down a ‘shock jock’ are very daunting but if you don’t fill up that space someone else will. See it as an opportunity to talk to an audience you'd never normally be able to reach.

Conspiracy theories are appealing because they suggest the world is being controlled, even if it's by a malevolent force. For many people, this is more comforting than staring into the chaotic abyss.

Arguing with conspiracy theorists is pointless as they're likely to assume you're 'in on it'. Instead, listen to what they have to say and calmly offer an alternative reading of the facts.

Scientific literacy is low among the public. Most have never heard of, or don’t understand, concepts like ‘peer-reviewed science’ or ‘testing a hypothesis’. But if scientists engage with the public through the media in a simple, clear and engaging way, the audience will become more scientifically literate.

Don’t feel you have to accept every invitation to appear in the media. Check out the program and if you think their intentions are to ridicule you and your science, politely decline.